R.11 Incentives for Research & Development

Cities can stimulate research and development through incentives such as providing finance and space, offering technical support, business development and support with tenders.

[Context] Cities are breeding grounds for new products and technology to address local problems and opportunities. Such innovations fuel the urban economy and can be converted into tradable services, knowledge and exportable goods. Urban economies benefit from capturing value through import replacement while maximising exports. Innovation is often heavily underwritten by public financing, enabling inventors and entrepreneurs to take risks with the hope of recuperating public investment through taxes, private investment, job creation, intellectual property rights or dividends. Many nations invest somewhere between 1.5-3.5% of their budgets on research and innovation. City regions are increasingly doing the same. The region of Brussels and London metropolitan area invested 1.75% and 0.99% of their GDPs in 2015. Cities are intensely competitive in terms of being at the forefront of innovation and each must create the most suitable atmosphere to incentivise cutting edge research and development while attracting businesses and retaining established ones. Incentives are therefore an essential tool.

[Problem] Research and development can involve a large amount of risk and uncertainty. Individuals and organisations that have innovative ideas do not necessarily have the resources to develop or exploit these ideas. Likewise, due to increased technical complexity and specialisation, organisations doing the research, design and development of innovative products are not necessarily those that are capable of producing them at scale. This can fail to capture the value of research and development to boost the local economy, while ambitious individuals move to other urban centres that are more encouraging of their skills. By contrast, research and development may have little benefit to the city where it is being developed which means that the research has little practical application. Finally, research and development in itself may be of little value to cities unless it is well embedded in a larger ecosystem of finance, communications, supply chains and even a local market.

[Forces] While innovation is difficult to predict, it is clear that conditions for research and development that lead to innovation can be nourished by third party actors such as public authorities, universities and private donors. Yet the fundamental questions arise from what kind of incentives will have useful results and which results will have value for the city. Is it focused on certain kinds of skills or knowledge such as computing, metallurgy or carpentry? Is the focus on sectors such as health, mobility (R.8 Moving Things Efficiently), IT, waste (R.6 Sustainable Product Cycles or N.2 Re-use of Material and Energy Flows), construction and/or aerospace? Focusing on developing specific sectors is referred to as economies of agglomeration. This will require making sensitive choices that will benefit some forms of research and development over others while ensuring that investment benefits the larger urban economy. Alternatively, there may not be a focus on any particular sector or activity. This is referred to as urbanisation economies, which is most attractive to larger cities but may result in neglecting emergent initiatives or weakening resilience. Investment in either approach takes many years to reap rewards and requires donors to have a long-term vision and patience. Incentives that do not suitably involve N.3 Mixing Complementary Making and Related Services or useful links to established facilities and organisations and N.7 Local Design and Prototyping may result in little systemic impact.

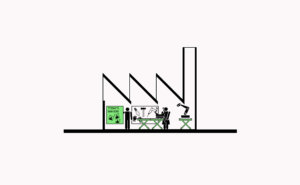

[Solution] Use incentives to kick-start change and innovation while penalising poor behaviour. Build where possible incentives around a local brand, R.1 Making Making Visible. Incentives can be framed within a local economic vision to help orchestrate efforts for collaboration to strengthen the local economy (such as between the public sector, non-profits, universities and private companies). R.10 Place-based Financial Levers can be used to help cluster businesses around a certain theme or activity (such as the circular economy or advanced engineering) which could include tax deductions or tax credits. Access to space is essential to test or develop ideas and prototypes. This may include: rental spaces (C.4 Diverse Tenure Models), P.4 Meanwhile spaces and Transitional Uses, P.3 Flexible Spaces for Making or long-term investment through R.9 Assured Security of Space. Proximity, or N.3 Mixing Complementary Making & Related Services, can ensure ‘thinkers’ and ‘makers’ can easily collaborate. Likewise, a P.8 Community Hub in Making Locations can help build informal relationships that spark new ideas while N.7 Local Design and Prototyping and P.3 Flexible Spaces for Making can bring ideas to life. P.7 Spaces for Development & Education may be necessary for building skills, particularly when new products also require using new technology. Any form of incentive could be followed up by a R.3 Curator to help guide future development and refine investment.

[Contribution] Add contributions here.