The new age of urban manufacturing?

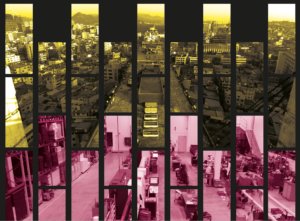

Aerial view of one of Brussels’ most diverse neighbourhoods, Heyvaert / ©Diogo Pirez

Can manufacturing return to cities? If so, how will it be different from the past?

Until the second half of the twentieth century many products were generated by local, regional, and national producers. This was largely due to the transport and accessibility to manufactured goods which created a kind of regionalism for manufacturing. Only the most valuable goods were exported over longer distances and the export was based on highly skilled labour rather than the cost of manufacturing.

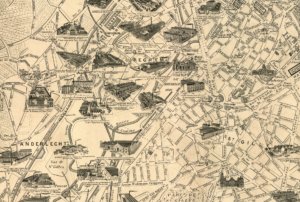

After the 1950s, with technical innovation and more effective division of labour, stable long-distance transport combined with automation, manufacturing shifted dramatically to places where production costs were lowest. This is based on a spreadsheet analysis of labour costs and land value and assumes that there is no added value in the production process beyond the value of the final product itself. It also assumes that skilled labour can be reproduced anywhere in the world. The industry that stayed (or was forced to stay) moved to the edge of town, to freeway junctions and cheaper land and eventually drifting off-shore. Functionally obsolete, the extensive intercity waterfronts, railway yards and warehouses now lie dormant or have radically changed function. “Off-shoring” of work led quickly to wide-scale unemployment post WW2, increased wealth disparity and a loss of high skilled labour as jobs and apprenticeships moved out of urban centres.

A relic of the industrial age, but without an industrial future. Tour et Taxis (BE).

A relic of the industrial age, but without an industrial future. Tour et Taxis (BE).

Led by cities and developers promoting the service economy, urban regeneration has targeted former industrial areas bringing new residents, offices, retail space and entertainment districts. Certainly this offers functions that were not previously available, however the focus on the service and creative economy has not replaced many of the jobs that left with the industry. Many former industrial cities now suffer from high unemployment, in particular for low skilled workers and young people.

The result for many parts of Europe is also a reduction of technical knowledge, a dependence on imports and a need for job diversity that can adjust to global economic volatility. The current focus of regeneration on the service economy misses a significant opportunity. It is the opportunity to have a diversified employment base, to have a local economy driven by production and creativity, filling the gap left with de-industrialisation, providing jobs and apprenticeships to young workers and helping to rebuild communities. Themes such as “reshoring” and “reindustrialisation” are becoming common parlance for policy makers that intend to bring manufacturing back to Europe however what this is remains unclear. Is it just about brining back the same industrial processes that were “off-shored”? Will they cluster back into the urban areas that lost the jobs and industry in the first place or will it be located on the cheapest available land miles away from urban centres? Two themes are becoming increasingly clear that could make cities the most logical choice: technology and value.

Firstly if Europe intends to compete against other global economic blocks, then manufacturing is going to be a significant talking point: the best place for cities to start is to think in terms of basic self-sufficiency. Popular themes such as the circular economy are pushing in this direction with valuation of resources particularly at an urban level. Circular economy as a theme remains very poorly defined at a city scale.

Secondly new tech is bringing new opportunities that could bring a lot of manufacturing closer to home. What this means in terms of production, jobs, space and so on remains very poorly researched.

Opportunities:

Technology. We are now entering into a new age of industrial technology, what some call the third industrial revolution. Many fairly simple objects that were produced in low cost production areas can now be manufactured locally with freely accessible technology with the likes of 3D printing, CNC routing, decentralised bio-methane production and so on.

Resources. With an increasing common awareness of the faults of linear production (pressing evidence in the recent Paris climate talks), we need to understand how to take advantage of locally produced and consumed resources. This is about a circulation of resources based on 21st century technology.

Consumer demand. The need for on-demand products as well as desires for increased quality have led to a number of companies recently relocating manufacturing back to Europe. Also an increasing desire for personalisation.

Local dynamics. The rise of the social economy and the development of FabLabs, Hacker Spaces and the maker movement as well as the growth in social enterprises and localist movements demonstrates the move towards local production.

Politics. There is increasing pressure to lower unemployment rates across Europe. In the United Kingdom the ‘March of the Markers’, advocated by the current national government, has focused on promoting manufacturing jobs in the UK.

New social systems. The current methods of production and consumption produce vase amounts of waste and are damaging the environment. This ranges from energy to resource consumption, mobility to food and work and proves that we are dealing with much more than a technical problem but rather a social problem.

Mark Brearley, professor at The Cass in London at the 2015 ISOCARP conference in Antwerp.

Transitions

Transitions back to a industrial areas will not likely happen overnight even with fantastic new technology or hole-proof business models for material re-valuation. Existing land use policy, established contracts and even consumer behaviour takes time to change . This leaves us wondering – what are the conditions required for a transition to a new urban industrial economy?