Profile: Sewoon – a City of Making (in Seoul)

Urban Manufacturing Next poster cover – Professor Jie-Eun Hwang

South Korea has been known as one of the Asian miracles - moving from one of the world's poorest countries to one of the richest within a single lifetime. Like Japan half a century earlier, it grew its industrial ingenuity on adapting Western technology and then building a culture of technical expertise and innovation. Yet like in many Western cities, Seoul is also seeing considerable real-estate pressure, which is particularly problematic for small-scale manufacturing districts. Sewoon, located less than 1km from the CBD, is a site which is showing friction between real-estate and making and demanding a clearer idea of what vision the city has for its urban economy.

The Cities of Making team was invited by Professor Jie-Eun Hwang to contribute the Urban Manufacturing Next forum focused on an inner-city neighbourhood called Sewoon Sangga, rich with small-scale manufacturers yet under frightening pressure to be gentrified. The site has long lived quietly next-door to one of the city’s more intensely occupied financial districts. Yet after cases of violence between small business owners and real-estate developers, activist and academics began to take a more interest and a ‘hands-on’ approach to understanding how the area functions and relates to the urban economy.

The forum* was aimed at pausing to reflect on the benefit of having such manufacturing district within a central part of the city and look at tools and levers for supporting the neighbourhood. Adrian Vickery Hill from Cities of Making joined Adam Friedman (The Pratt Institute / Urban Manufacturing Alliance) and Christian Krug (VDI – The Association of German Engineers) to provide external input into the state of the urban manufacturing, supported generously by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

While Seoul’s urban form is radically different from European or North American conditions, we found that there were considerable similarities in terms of how public authorities and residents relate to these productive neighbourhoods.

Seoul, a 20th century city of making

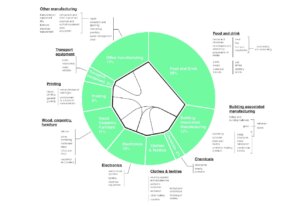

After almost two centuries of Japanese influence and then a decade of war, Korea was rendered one of the poorest countries in the world. With the Korean War tragically splitting the peninsula in two opposite facing regions, South-Korea tuned its gaze across the Pacific Ocean, underpinned by American aid and technological influence. The peninsula has no considerable natural resources, however ruled by an ambitious series of regimes focused on development, South Korea took the only significant resource at its disposal – technology – and began reproducing and then improving imports. This technical knowledge grew both large organisations that centralised production (such as Panasonic and Hyundai) while also ushering an ecosystem of smaller makers, often clustering activities (metal work, clothing, electronics, woodwork and so on). The larger companies, called chaebols, developed their production centres as small closed villages on the edges of the city. The smaller makers remained closer to the city centre as it meant better access to markets, clients and housing.

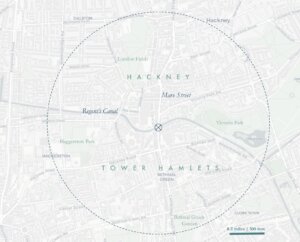

3D model from SMG.

Sewoon Sangga, an unforeseen utopia for (small-scale) makers

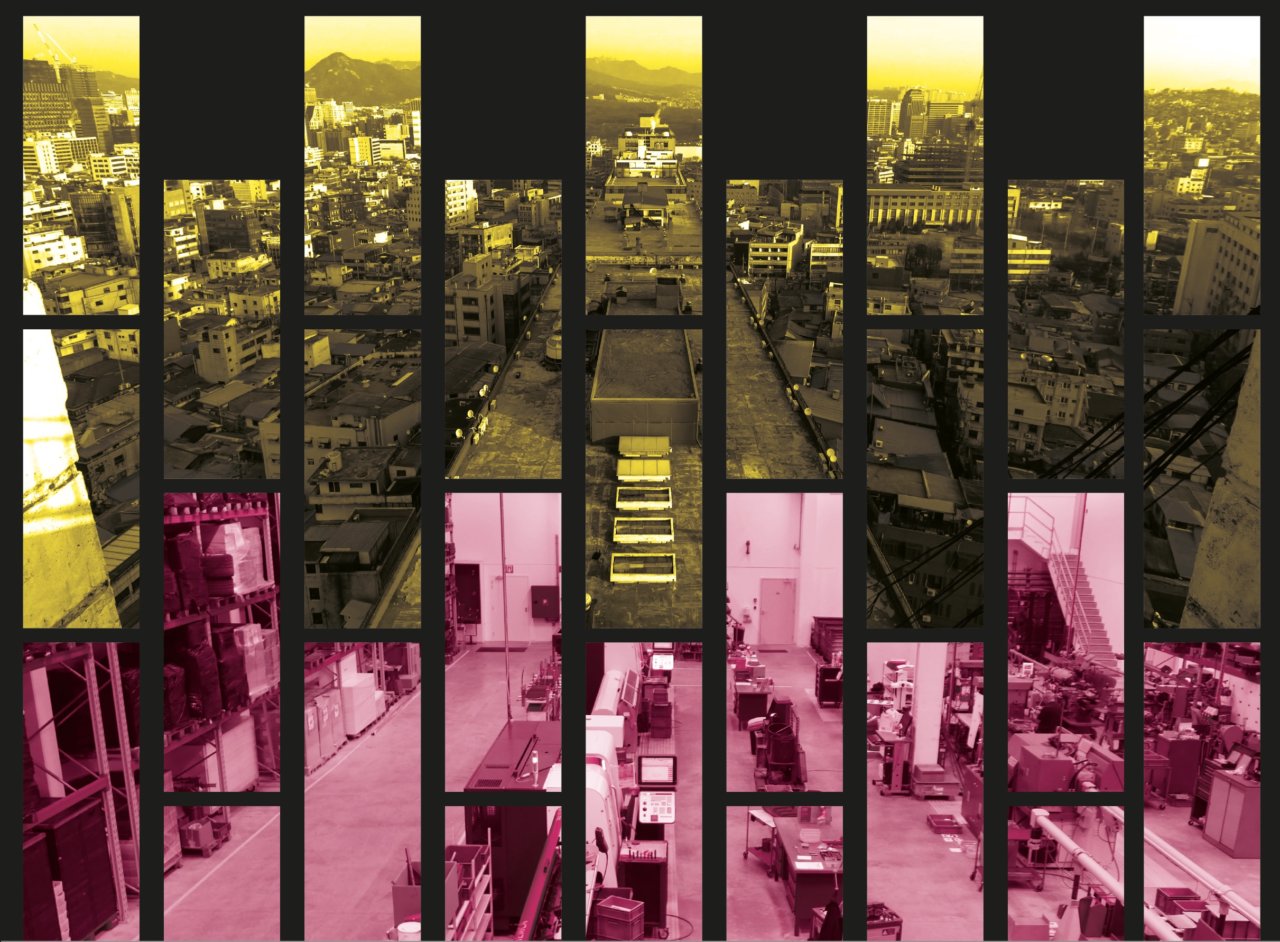

In the 1970’s, the rapidly growing Seoul began developing ambitious infrastructure projects. One such project, Sewoon Sangga*, conceived of building a 1km long building that would connect two sacred sites. This modernist Athens Charter inspired building complex involving a raised pedestrian that would allow luxury modern apartments to be located five or more stories above the adjoining ‘informal’ neighbourhood. Like many modernist ideals, conditions changed radically once the spaces began to be used.

Almost five decades later, the Sewoon Sangga project has turned into a haven for small makers and retailers making and selling electronics and mechanical parts. Adjoining the building is a former slum which is now now to 1000’s of small manufacturing businesses operating with a vast range of materials from wood, textile, metal, glass, electronics and so forth.

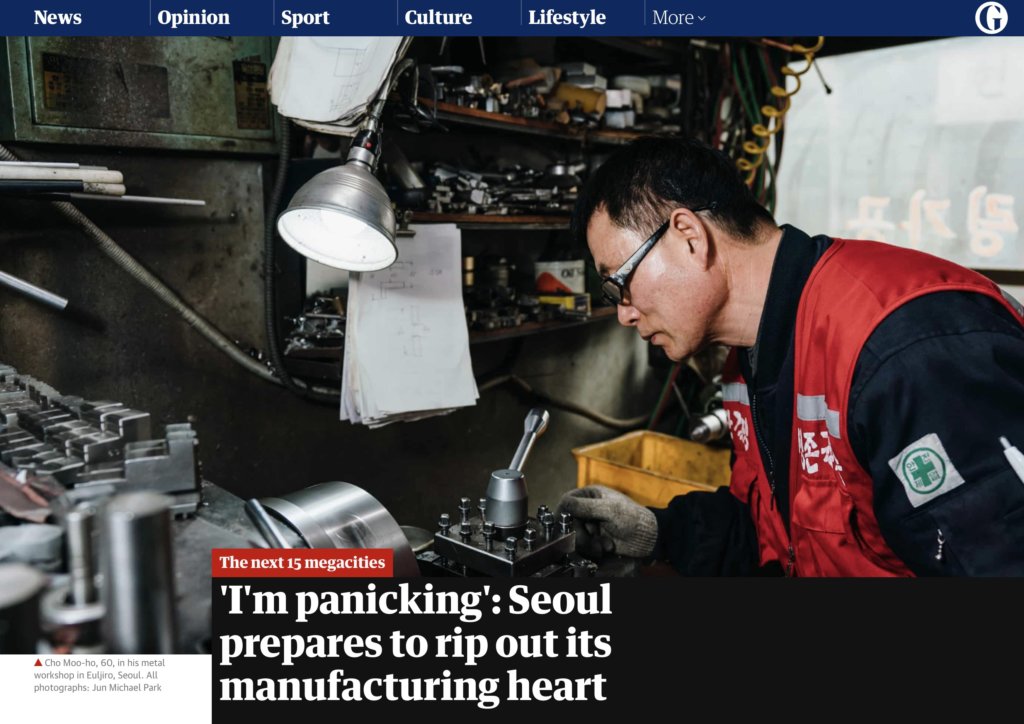

In practice, the makers form a network, performing a small task, but rarely developing a product single-handedly. For example a simple copper bowl would require passing through a number of businesses – firstly to purchase the copper from a merchant, then having it cut, then moving to a specialist smith to punch the form and then finally to a business that buffs the final product. All of this can be done quickly and cheaply and involves specialists with intimate knowledge of their materials and technology – following the adage that one can enter the area with an idea and come out with a product. Hyundai is believed to prototype their first car in the area while Panasonic and LG continue to do prototyping here. European designers use the area to test and develop their products.

Pressures and a confusing vision for the local economy

Sewoon’s strength has been its small-scale makers – allowing flexibility, competition, redundancy and variety. However this is also its weakness. The estimated 10,000 small businesses have representatives, yet have little political power or the finance that the considerably larger developers have. Considering their distance from the metropolitan planning agency, and likewise the distance of the planning agency and the neighbourhood, numerous plans have been developed to simply raise the area to replace it with higher density development. Furthermore, the City of Seoul is also no monolithic organisation. In 2016 the then recently elected grass-roots oriented mayor signed a pact to stop gentrification. However this was to little avail. In practice it was found that the mayor holds far less power to halt or even slow down the real-estate sector, which in many cases are connected to the country’s largest companies. Almost overnight tenants were forcefully evicted, the manufacturers were being ‘unceremoniously wiped out’. For the areas that were successfully evicted, it took days for the bull-dozers to flatten the workshops.

The real-estate is not the only challenge. Young people are also far less inclined to take up the trade of their parents, leaning towards better paid and cleaner jobs in the services sector. This is a serious challenge as the older generation is troubled to pass on their knowledge or businesses. While some businesses do not have ideal working conditions, many see that they will not survive if they were to move to another location due to the nature of the informal relationships between the makers in the area. The municipality has set regulation which is making conditions from poor to unbearable such as the prohibition of replacing roofs. Living costs are also a challenge – while the real-estate boom is healthy for some, living close to work in comfortable conditions is far from a dream. Furthermore, understanding how the businesses operate requires building relationships and knowing where to find the most suitable manufacturer or material – in other words it will remain a challenge to connect the function and purpose of Sewoon with the larger population.

Supporting from the inside out

Until recently the Sewoon area has been considered both mythical and a curiosity to those from Seoul that know about it. However a range of public, academic and community driven initiatives have emerged which are exploring ways to protect the neighbourhood and were celebrated in the Urban Manufacturing Next event. In 2016, the City of Seoul committed finance to support a ‘cultural program’ – a first stage of building relationship between the inside and outside word. Some large infrastructure investment has been committed to the public space at the north end of the site, creating a stronger relationship with the adjoining royal palace. Small spaces have been developed including an incubator space, small exhibition spaces and small subsidised spaces for designers. In this way designers can apply for space in the area as a stepping stone for a longer-term solution. Independent community organisations, such as Listen to the City, are providing vital services in responding to the challenges of local businesses through art and culture. Researchers and academics have also found a place in mapping and understanding how the larger informal network of businesses operates and particularly how they link outside of the area.

Learning from Sewoon

There is a vast amount to learn from Sewoon. Looking at the ecosystem of makers may appear reminiscent of the mechanics of a medieval city with neighbourhoods of tightly packed specialist makers and market spaces. This has been lost in Europe with the advent of the industrial revolution and 19th century effort to ‘sanitise cities’. If anything, Sewoon shows how there is a strength in having a concentration of making in the heart of the city. Recent efforts to integrate the area into the city both spatially and culturally have proven popular yet there is a question about how far the gentrification process should go before other forms of speculation or tourism may have a negative role on the the neighbourhood’s core activity – manufacturing. Then there are typical questions shared with European cities such as who should be financing the support for the district, how much should the public sector intervene and how can the district be fairly represented when facing the prospect of redevelopment?

Surprisingly, the Sewoon case study has much more in common with European examples than what meets the eye. There is much to learn from this rapidly changing site and the vast variety of external initiatives that are being tested.