London: making space for manufacturing in the city

Hackney Wick, as space in transition / ©Adrian Vickery Hill

This week the RSA releases a new report assessing the role and current state of manufacturing in three of Europe’s urban centres. Compiled by a consortium of partners in London, Brussels and Rotterdam it forms part of Cities of Making, a thirty-month programme exploring the future of urban based manufacturing in European cities.

The report argues that, despite significant changes to the scale and makeup of manufacturing in the three cities, the sector still has an important role to play in their economic and social fabrics. Perhaps even more so in a future which promises new opportunities from technological developments, such as distributed manufacturing and automation, and one in which cities must address significant environmental challenges, including climate change and resource depletion.

Here are seven key takeaways from the chapter on London:

1. London is still a city which makes

Despite perceptions that ‘we don’t make anything here anymore’, the manufacturing sector in London remains significant.

Today it employs 114,000 people – a figure equivalent to the population of Rochdale – a larger number than in city regions which might more usually be recognised as manufacturing hotspots, like Greater Manchester.

Historic decline as a result of deindustrialisation has led to claims that the sector is in free-fall. However, projections based on these trends do not fully consider the need for manufacturing in the city. Whilst the sector has changed, its services are still required. Indeed, rather than continue to decline, in the last few years employment levels have plateaued.

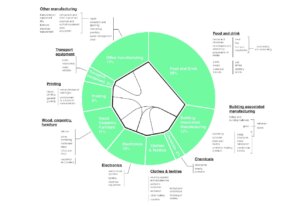

2. London’s manufacturing sector is diverse with a high proportion of small businesses

As has been the case historically, London’s manufacturing sector is made up of many kinds of activity, from jewellery to automotive production. Many of these activities are focused close to the end of the production chain, reflecting the sector’s role in servicing both residents and other businesses in the city.

Four sectors make up the bulk of activity: Food and drink production (24,000 employees, contributing £2 billion to London’s economy). This includes large companies like Tate & Lyle, smaller artisan production, and convenience food. 14,000 people are employed in the manufacture of fabricated metal products, including nearly 4,500 producing metal doors, windows or structures, supplying London’s renowned architects. Printing production accounts for 9% of all manufacturing activity in the city and provides to businesses from museums to financial firms. The almost 6,000 people employed in garment manufacturing produce for Asos through to Alexander McQueen.

London has a higher than average proportion of micro manufacturing businesses, with more than 87 per cent having fewer than 10 employees. Almost a third (29 per cent) of employees in the sector work in these kinds of enterprises, a figure more than twice that of many other UK regions.

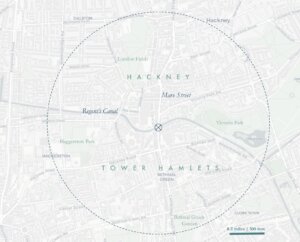

3. Manufacturing takes place all over the city.

When asked where manufacturing takes place in the capital, many people will likely think of the large industrial spaces, such as Park Royal in north west London, or other clusters in areas like Greenwich and the Thames Gateway. But many the c.14,000 manufacturing firms in the city are also to be found in smaller sites, such as in railway arches or at the backs of high streets. My colleague Fabian Wallace-Stephens has created an interactive map which allows you to explore this geographical spread in more detail.

4. This diverse and dispersed makeup can make it difficult for the sector to be seen and heard

Despite manufacturing taking place all around London it can be easily missed. Activities often take place behind closed doors or in locations that residents don’t see. Many Londoners do not realise what is being made in the city. Worryingly, many decision makers don’t know this either, with councils often having little information about manufacturers in their boroughs.

This lack of visibility is problematic. Firstly, because it strengthens the misconception that ‘nothing is made here anymore’, and secondly because it leads to the sector being unrepresented in decision making.

This is reinforced by the small size of many manufacturing firms. These firms have little time or resource to engage with policy and decision making. Without strong representation their voices go unheard, and those with fewer connections are likely to fare worse- hardly the vision of an inclusive economy.

More needs to be done to hear their voices and to support collective action. An example of this already taking place is the Affordable Workspace Manifesto from East End Trades Guild. This collective of small business owners in East London, including manufacturers Square Root Soda and Calverts printers, have been lobbying Hackney and Tower Hamlets council candidates to back their calls for affordable rents.

5. London has the potential to capitalise on the next wave of manufacturing technology and innovation…

In its Industrial Strategy the government has laid out ambitions for a strong and innovative manufacturing sector which capitalises on new technologies. There is great potential for London in this. The city has world class research universities and draws talent from around the globe, and it is already home to innovative companies like Brompton, who are not only producing in the capital but also creating a vision for transport in our cities.

With a new industrial revolution on the horizon, characterised by greater connectivity, automation and new forms of production such as 3D printing, opportunities are emerging for different models of manufacturing. Distributed and smaller scale production are anticipated, and London is already home to businesses developing this potential. The city has over 50 open access workshops and makerspaces. These enable people to access support and technology and are a focus of entrepreneurial activity.

The sector can also support the move to a more sustainable city. The size of the city and skills available provide an excellent opportunity for developing new business models which shift the way goods are produced and consumed to more circular economy models which implement repair, remanufacture and recycling.

6. But the potential is being constrained, most evidently by a lack of space

There are gains to be made from these emerging opportunities, and London is well placed to help the UK to capitalise on these, but it must act to do so. Despite the success of current businesses, there are significant pressures on London’s manufacturers.

Most evident is the lack of space for their activities. Between 2001 and 2015 industrial land equivalent to around 1800 football pitches was transferred to other uses, more than double benchmarked figures. Today vacancy rates are low in industrial spaces across the city. Together with increasing rents and the threat of redevelopment these are affecting businesses’ ability to thrive.

Machines Room, a makerspace and incubator in East London, is one of the latest to suffer from soaring rents. They have recently had to leave their premises and the search for a new site has proved almost impossible. Larger established businesses face similar challenges. Truman’s Breweries, who have been looking for a suitable second site for over five years, have noted that the lack of space is the most pressing concern for their businesses.

The lack of capacity is stifling innovation and growth. Whilst policy direction has changed to curtail further loss of land, more is needed to integrate the spatial requirements of the city’s makers into the developing city.

7. London’s industrial strategy must present a vision for what manufacturing can do for the city

The loss of industrial space is a symptom of a lack of vision for manufacturing in the city. The sector is important now, as an employer, as a source of innovation, and as a supporter of other activities. It has the potential to also play an important role in achieving London’s ambitions to become a sustainable and inclusive city.

However, a lack of vision for this future, combined with its relatively small size and dispersed nature means that is struggling to fulfil this potential. As local Industrial Strategies are developed London’s policy makers should be working together with the city’s manufacturers to shape a stronger and more holistic view of what ‘making’ can offer the capital in the 21st century.

___

Alongside similar analyses of the state of urban manufacturing in Brussels and Rotterdam, we hope that this overview of the sector in London stimulates debate about the role of ‘making’ in the city.

In a next phase of work we will be exploring three aspects in more detail: governance and policy for supporting the sector; opportunities for harnessing resources and technology to develop more sustainable production; and space and building designs for supporting modern urban manufacturing.

- Download Cities of Making: London (PDF, 1.9MB)

- Download the report – Cities of Making (PDF, 9.7MB)

___

Text first published by The RSA.