So, why do we need manufacturing in the UK?

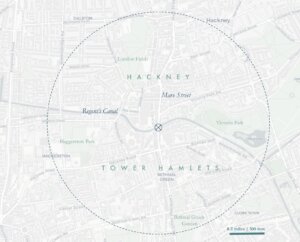

Hackney Wick’s rapid transformation from industry to other functions / ©Teresa Domenech

After years of de-industrialisation and a concerted focus on developing the knowledge economy, it is unsurprising that manufacturing has something of an image problem in the UK. Increasing however, technological, economic, social and environmental issues are converging to make the time ripe for re-evaluating this perception. This blog explores some of the arguments for supporting manufacturing in advanced economies, like the UK, and forms a backdrop to Cities of Making, our programme of work on urban manufacturing.

1. Manufacturing, the driver of innovation

Innovation in manufacturing has been the main driver for increased productivity in economies. In the UK the first and second industrial revolutions changed the way we produced and consumed goods. These shifts, and the ensuing economic growth, catapulted the nation onto the world stage and dramatically changed our communities, our jobs and our environment. Even with the increasing importance of the services sector in the last few decades, many of the productivity gains we have seen are as a result of product innovations in areas such as communications and computing.

Where goods were once designed and produced within relative proximity, the rise of globalisation has led to a splitting of their development and their production. In developed economies like the UK we have kept, on the whole, the ‘valuable’ bits of innovation: research and development, and design; and shifted manufacturing to areas of the world where labour and production costs are cheaper.

We have arguably done well from this. But there are those who think that this approach will prove to be increasingly problematic if developed economies want to continue benefitting from high-tech innovation. In the US, Harvard Professors Willy Shih and Gary Pisano talk about the erosion of the nation’s industrial commons, the phrase they have coined to cover the common skills, understanding and networks which make manufacturing clusters more than the sum of their parts, and argue that this loss is and will stifle innovation within the States. They contend that it is not only low-skilled labour that has been outsourced, but that sophisticated processes too are being lost, the production of batteries for electric cars for example, and along with them their skills and infrastructure.

At the same time the countries to which such manufacturing has moved are benefitting from their own industrial commons and increasingly developing products, not just manufacturing them. This is the attraction of places like Shenzhen, the ability to rapidly develop, prototype and produce hardware technology. For certain industries dividing manufacturing from design may be short-sighted.

The UK then, like the US, is in a competitive space if it wishes to attract and retain talent, and benefit from the competitive advantages which innovation can offer. Creating a climate supportive of innovation is about more than just shiny co-working spaces, entrepreneurs need to have access to a host of resources to generate and bring new ideas to market: investment, business support, skilled employees and skilled contractors – manufacturers included. Investment in achieving this can be seen in examples like the High Value Manufacturing Catapult and the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre, but in reality hardware entrepreneurs faces high barriers to enacting their ideas in the UK. Hubs like the Central Research Laboratory in West London are beginning to emerge in order to tackle this problem, but much more support is needed.

2. Jobs, and for who?

Given the scale of employment which manufacturing once delivered in this country it is unsurprising that many conversations about manufacturing centre on the question of jobs. De-industrialisation and the ensuing structural unemployment it brought was devastating for individuals and communities around the country. Its effects are still being felt today. For some here and across the pond, it is the re-creation of these many and stable blue-collar jobs that we should look to manufacturing to provide. However, we must exercise caution when looking to recreate manufacturing times past: the scale of employment in manufacturing has dramatically declined, from nearly 30% of all UK jobs in the 1970s to under 10% today, and doesn’t show any signs of growing back to previous levels. Automation and changes in manufacturing technology will also mean that the jobs in future will look very different.

This is not to say, however, that jobs are not pivotal to the argument for manufacturing. Instead, we need to focus on the quality of the jobs and who might benefit from them. Whilst the scale of employment is much lower than it once was there are signs that manufacturing can deliver decent jobs, the typical (median) weekly earnings for a UK worker in manufacturing are £555, slightly higher than the median earnings for all employees. Still, job quality and pay is variable across different manufacturing activities, compare a typical garment machinist to a car factory worker, whose average weekly earnings are £376 and £665 respectively. Manufacturing businesses have the potential to support different kinds of jobs and skills, but this is far from guaranteed and we need to be having a much more honest conversation about what jobs manufacturing will offer us in future.

3. A new industrial revolution

Developments in technology combined with rising overseas labour costs are making the reshoring of manufacturing more appealing and viable. Adidas, for example, have invested in automated production in Europe. New technologies, such as additive manufacturing, and the potential they bring for mass-customisation and redistributed manufacturing are also shifting consumer trends. Companies such as Unmade and Autodesk are signalling the potential for once again manufacturing close to the customer in the UK, and blurring the lines between design and manufacture, and manufacture and retail. If the advances promised by Industry 4.0 are realised, these factors could once again bring manufacturing to our doorsteps and we should be ready to make the most of this.

4. Rebalancing the economy

In the wake of de-industrialisation the UK built an economy heavily reliant on the finance and services sectors, and one which is very concentrated in the south east. The fall-out from the financial crash, the uncertainty of Brexit, and the realisation that the trickle-down economics is not working for large swathes of the country calls into question whether this is the best approach. As a result there is increasing interest from government in devolution and in building resilient and inclusive local economies. Industrial Strategy is even making a comeback. These are significant opportunities for rebalancing our economy, both in terms of sectors and regions, and manufacturing could play an important role. But in reality we aren’t seeing Osborne’s March of the Makers, instead manufacturing’s share of UK GDP has stagnated at around 10%. Rather than being symptomatic of the lack of importance of manufacturing this arguably shows just how much damage has been done to UK manufacturing over the past few decades, something we should no longer ignore.

5. Building a resilient city

We are witnessing large scale global challenges: climate change, resource scarcity, mass urbanisation. It is clear that many of the structures on which our economy is built will not continue to serve us and need radical rethinking for a resilient and prosperous future.

Whilst much of the economic boom enjoyed since the industrial revolution has been built on the way we produce and consume goods, we now realise that we need to change our linear take, make, waste model which seriously threatens the foundational environment of our planet. A shift to a more circular and sustainable economy is increasingly discussed; at its core is a requirement for us to change the way we produce and consume goods, including the reuse and repair of goods.

We are seeing examples of this, from repair gurus to the servitisation of products, but we face a real challenge to put this theory into practice at scale. Given that production is key to this change it follows that manufacturing capacity and skill will be core to this shift. If we are to radically rethink our production then we need to grow our capacity to make and maintain goods in a much more local fashion than we have seen for over a century.

6. Making our future

Manufacturing has had a tough time in the UK over the last few decades, but it is clear that it should have a seat at the table as we think about the future of our economy and society. We need to be careful not to fall into the many nostalgia traps which lurk around manufacturing; it’s not all steelworkers and jobs for life, nor is it all craft beer and workmen’s jackets. It’s a more complicated picture than is often presented and one which we should be looking at even more closely if we are to unpick the rhetoric from the reality and, importantly, the potential. It’s time to think seriously and pragmatically about what manufacturing can do for our country and for the places within it.

Article first published by the RSA.