Brussels’ manufacturing: a brief history

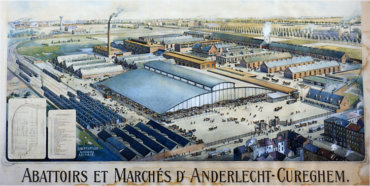

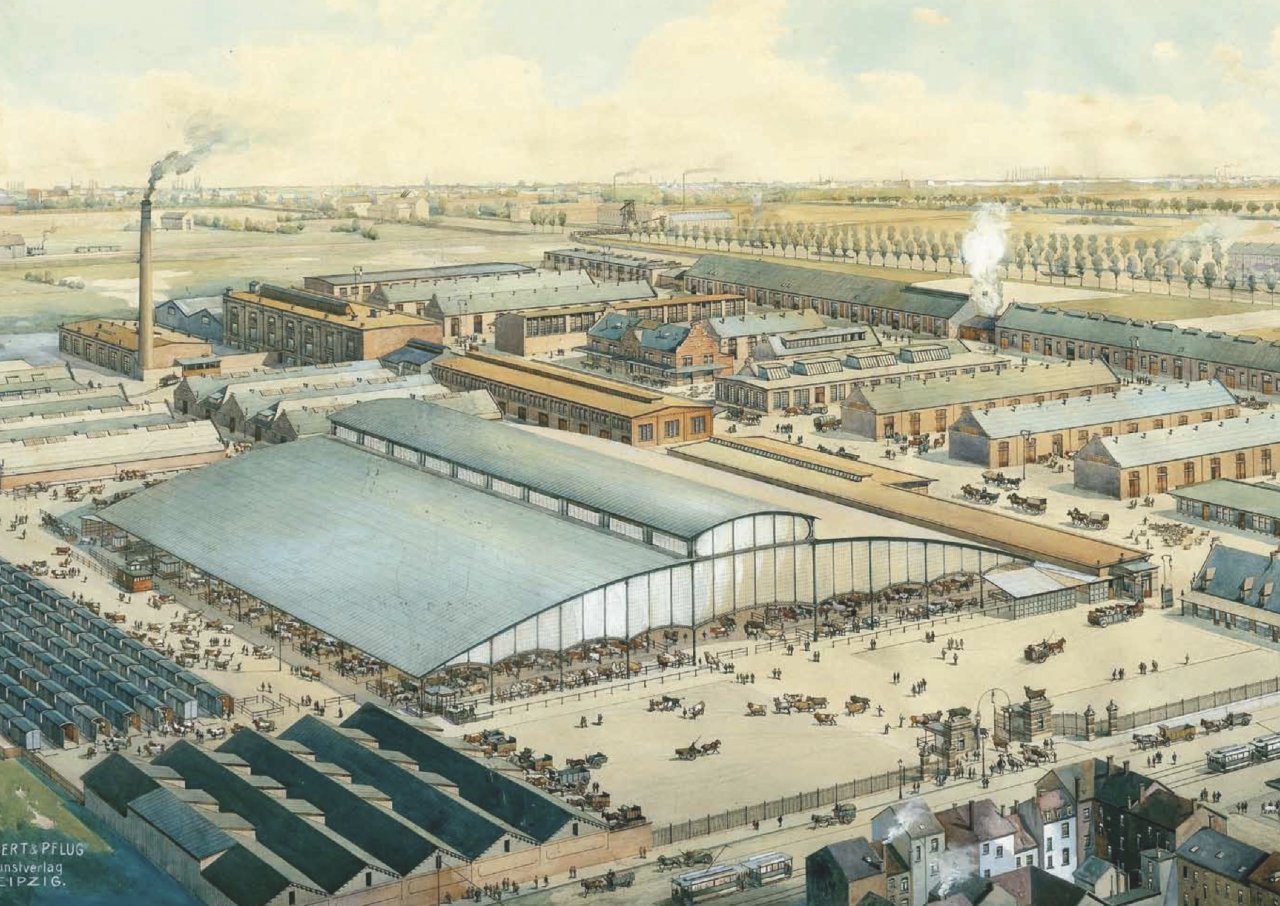

Eckert & Pflug 1910, plan for the Brussels’ abattoir.

From being a pioneering industrial centres, claiming more than half of the city’s jobs, Brusels now contains one of the lowest rates of urban manufacturing in any European city and has arrived at a new crossroads in its productive future.

From early manufacturing to the Industrial Revolution

Brussels’ ‘manufacturing spirit’ can be traced to the region’s infamous Flemish textile production from the 13th century. In the 16th century, the Dukes of Brabant favoured the city over many others for their court, marking its economic and political role thereafter. Over various dynasties, the political power remained linked to the seat of the Duchy until the Belgian revolution of 1830 where Belgium was formed as a buffer state and Brussels was proclaimed capital. Saxon born King Leopold I, married the daughter of King George IV (of England), accepting the throne in 1831 and quickly brokered the first import of revolutionary rail and industrial technology, pioneered in the UK. Brussels claims mainland Europe’s first railway.

The 18th century Charleroi Canal enabled coal to be imported on a massive scale and the mechanisation of industry led to the appearance of foundries, engineering and metalworking companies along with the development of the railway network. The city also attracted administrative and higher class workers that represented both a valuable consumer and investor market, thus kickstarting local manufacturing. Manufacturing sectors included vehicle bodywork, printing and porcelain obtaining international reputation while chemical processing developed to supported related industries such as textiles.

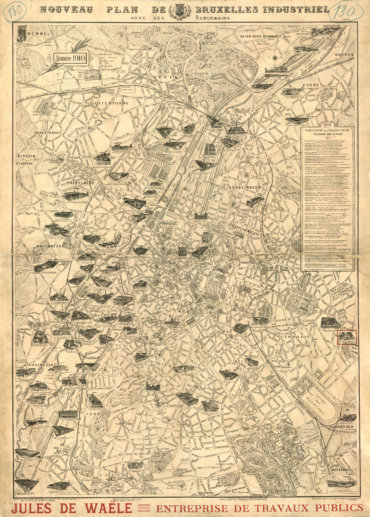

During the 19th century, industry – and particularly metallurgy – grew with a reliable cheap source of coal from the Meuse Valley. Urban populations increased rapidly, Brussels grew from 210,000 in 1846 to almost a million a century later. Furthermore, Belgium laid out the continent’s densest rail network that created one of the first intercity commuter workforces, linking the densely populated agricultural hinterland with the city. These factors turned the capital into the largest industrial centre in Belgium with the highest concentration of industrial workers: a title the city retained from 1890 until 1970. The Canal area, in the lowest part of the city was most attractive for manufacturing as it was connected to train stations and raw materials supplied along the canal (such as coal) while forming a richly knit urban fabric of housing and manufacturing.

Whereas the larger (former) industrial areas are located along the canal zone such as Buda, on the northern fringe and Anderlecht-Forest on the southern one, small and medium-sized family businesses are located on either side of the central section of this axis. It was thanks to the emergence of new industries such as crockery production, carriage-making and printing (18th century) that a large number of factories were built just outside of the medieval walls, in places such as Anderlecht and Molenbeek which lined the canal. While manufacturers grew up along the central axis of the Senne valley, other small to medium activities spread within the very dense urban fabric, filling in the interior of housing blocks and replacing private gardens, adapting existing residential buildings or colonising vacant plots. That process has created highly mixed and unplanned manufacturing neighbourhoods that are still visible today in areas such as Cureghem, Saint Gilles, Evere and others that emerged in the city’s rapid late 19th century growth period.

Manufacturing peak (1900-1960)

Industrial Brussels reached its climax during the early 20th century, focusing on high skilled labor and a conveniently high concentration of clients living in the city. A diversity of small scale manufacturers were developing in Brussels especially thanks to production of machines (vehicles and engines) and consumption-oriented businesses.

After the Second World War, the economic structure of Brussels was still in good shape compared to other European cities. The Belgian capital was developing with a widening middle class, spurred by economic growth, public work plans and mass consumption. The average size of companies significantly increased, with the investments of multinational organisations in Brussels’ manufacturing4. The city managed to keep a wide range of activities. By the end of WWII the major manufacturing sectors included (by ascending order) construction of machines, clothing, agro-food, metallurgy, chemicals and printing/binding – directly employing some 166.000 people in 1960.

Deindustrialisation, a Brussels-Capital Region and neoliberalism (1960-2010)

Since the second World War, urban manufacturing occupied large amounts of space while employing low qualified labor. Post war economic development saw native Belgians shifting into the tertiary sector and thus demands for skilled workers attracted immigrants initially from Greece, Spain and Italy and later from Morocco, Turkey and the former African colonies – with certain assumption that these workers would later return to the their countries of origin when the work dried up.

While the aftermath of the second world war was blowing life back into the industrial sector, a new industry emerged: the services sector. The arrival of European institutions in the 1960’s and the large ecosystem of lobbies and services attached to it have taken over various former workers’ neighbourhoods and industrial zones in the east of the city while bringing with it higher paid jobs. Furthermore the federalising of the country in the 1980’s, resulted in a complex bureaucratic stew that would also be headquartered in the city and land largely on former industrial land or blue-collar neighbourhoods around the north and south train stations. Finally, the Brussels Capital Region (RBC) was created in 1989, drawing a 160km2 island within the Flemish region, amassing 1,2 million people into almost a city state.

Brussels and manufacturing today

Brussels, despite a formidable place in Europe’s industrial heritage, has now one of the smallest industrial sectors (as a percentage of the economy) while also having one of the highest GDPs per capita in a European city. Industry accounts for around 6% of the regional economy, for which 3% can be attributed to manufacturing. The sector consists largely of the construction/assembly of vehicles (cars and plane parts), chemical refining, agro-food processing and a large number of smaller specialist businesses. Despite some four decades of steady decline in the industrial sector9 the sector appears to have a minor but stable place in the larger economy. Beyond pure manufacturing, there are a range of other sectors that have also an important role to play in terms of manufacturing such as the construction and recycling.

The region is a compact 160km2 city-state while having a significantly larger daily urban network that depends on the city yet which the city has little influence over. The city attracts some 330,000 commuters per day into the city (¼ of the resident population) that work largely in the services sector yet also place serious pressure on the mobility network in and out of the city. The industrial activity on the other side of the border is significantly higher (in the order of 10% of employment) and contains a range of manufacturing sites that depend on Brussels yet is largely ignored by regional planning. Due to this regionalism and politicisation of territorial planning, some of the Region’s planning agencies are attempting to avoid losing further productive space or manufacturing jobs.

The shift from Brussels’ industrial heritage to its largely services based economy has left a number of unanswered riddles. Firstly, much of the migrant population that arrived since the 1960’s has remained and grown, yet some of the communities (and their families) have struggled to adapt to 21st century service oriented jobs and now are heavily represented in the city’s 17% unemployment12 (24% for youth). Secondly, unlike many other European cities, Brussels’ inner neighbourhoods account for some of the poorest in the country made up predominantly of residents with immigrant heritage. These neighbourhoods (such as Anderlecht, Molenbeek and Schaerbeek) contain the most dynamic mixture of residential and industrial buildings, yet are under serious pressure from the real-estate market for gentrification. Finally, the fundamental narrative driven by the government (and supported by the real estate sector) is the need for housing without much foresight for the larger impact on the very informal local economies in these neighbourhoods (such as the second-hand car sales in Cureghem) or the types of housing that will be built (currently the market is focused on middle class housing).

New legislation is allowing housing to be included on land zoned industrial (ZEMU, see below), while the public actors driving the zoning have little knowledge of the types of productive functions (from manufacturing to logistics) that could be compatible with housing. The city’s manufacturers remain a quiet voice within the political arena and their needs are rarely prioritised over the needs of other land uses (such as housing, open space or commercial space). The question of what type of manufacturing is relevant to Brussels remains a serious challenge for many public actors and community groups whom are aware of the pressing tide of change facing the little remaining protected productive land currently zoned industrial.

In 2018 the Region has scheduled to launch an ‘Industrial Plan’, essentially to place this question on the political agenda. However the outcome of the plan may further stress the declining trend of manufacturing rather than look towards new forms of urban manufacturing. The implications of external forces such as Brexit and growth of the European institutions, will also place a heavy accent on housing and office space at the expense of affordable places for making.

Brussels is home to Belgium’s largest student and research population. The region educates some 104,000 tertiary students annually and employs 26,000 researchers representing 10% and 2% of the population respectively. It is also seeding the largest number of Belgian startups – some 2/5 call Brussels home. This proves a serious niche for both manufacturing (in prototyping or production) and the technical skills that come with it. Whether this remains in the realm of activities founded in the 20th century such as cars and chocolates or if it will move towards more contemporary high-tech production of sensors and decentralised value-added manufacturing, remains yet to be seen.

This text was first released within the ‘The Cities Report‘.