London: a Future for Making

London’s manufacturing base plays an important role in the city. Supporting this and unlocking its potential further requires a number of challenges to be addressed. For manufacturing to flourish in London a number of themes have been identified including the provision of suitable space, a greater focus on sustainability, industry voice in policy making and a more coherent vision for London’s manufacturing sector.

1. Providing space for making

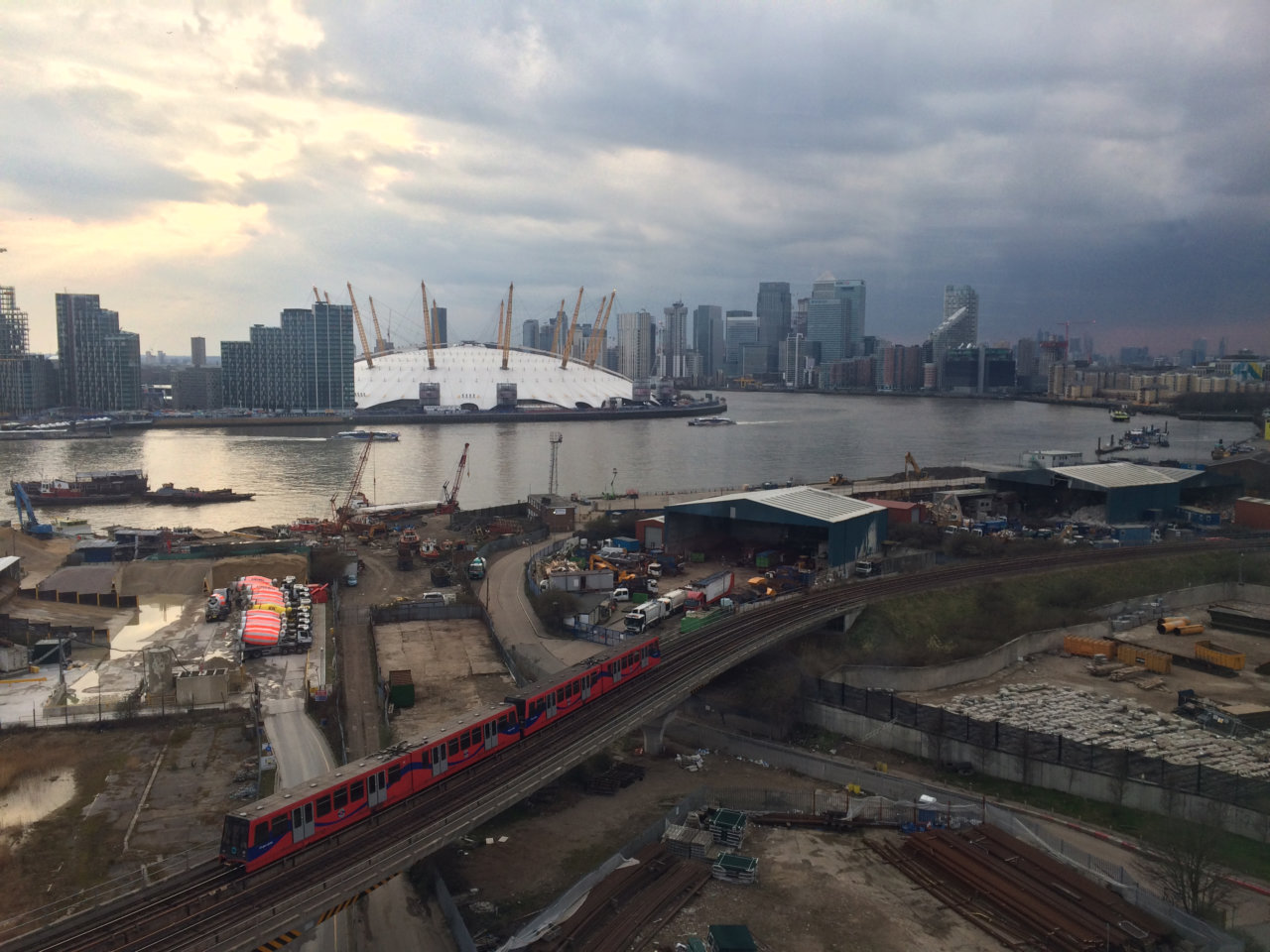

A bustling city like London must accommodate a range of commercial, domestic and civic activities. Spatial planning and architectural decisions made today will shape the future of the city. This is as true for the future of manufacturing as it is for the future of residential and civic spaces. Proper provision for these activities is crucial to the future success of the city’s manufacturers.

The Draft London Plan shows ambition to address the provision of industrial space. It seeks to prevent further net loss and to ameliorate the available space through the intensification of existing industrial spaces and through provision of new mixed use developments, which bring industrial and other uses together. This step demonstrates the GLA’s recognition of the importance of protecting industrial capacity within the city and is very much welcomed.

However, it is unlikely that this alone goes far enough in mitigating the threat of insufficient space. Whilst the policy goal is that there will be no net loss there will be loss in some areas as land is consolidated and shifted within boroughs. These movements will continue to be felt by businesses across the city. The largest concern is that in protecting industrial land boroughs are likely to focus on SILs and LSISs. It is right that these segregated spaces are duly protected, but it is important to also recognise the impact that the loss of undesignated industrial space has. These sites, at the backs of high streets for example, provide important and distinctive space for business and play a role in the vibrancy of high streets and town centres across the city. Calverts, for example, are situated on this kind of site, as are the units in ‘Maker Mile’ just around the corner.

Design and proving concept

The Draft Plan places emphasis on intensifying current industrial land, and on creating more mixed use developments, where industrial, residential and/or other employment uses are co-located. Both of these routes offer potential for tackling the constraints of space in the city, but bring their own challenges in design and execution.

Intensification involves increasing the efficiency of the existing stock of industrial buildings. Some examples of this exist in the city, like Segro’s multi storey warehouse in Heathrow that houses industrial units on multiple levels. The company are planning another of these at a development in Meridian Water in North London. Examples similar to this exist in other countries. However, it will be important to understand which activities these developments are providing for, and specifically how manufacturing space can be made available, not only space for warehousing and logistics.

The second route brings together industry and residential or other employment space in ‘mixed use’ developments. This is increasingly appealing as space in the city becomes ever more in demand. However, there are significant challenges in doing this, indeed the existing land use classifications were implemented in order to prevent mixed activities being unhappy neighbours. Industry can be noisier or smellier than residential activity and there is often a need for industry to operate around the clock or to receive early deliveries. On a segregated industrial estate this causes little concern, but when residential developments are nearby or co-located with industry, issues can arise. Where this occurs it is more likely that the industrial occupiers are required to compromise their activities. Whilst these are valid concerns, it should also be remembered that industry and residential buildings already exist together all across the city, and that these concerns can be overcome and managed through good design and governance.

Employing high-quality design will be critical to making these ambitions for mixed use and intensification work. Business requirements like yard space and access must be taken into account, as must residents’ need for tranquillity. The challenges to success may not lie solely in design however, but also in financing. The real barrier may come in proving the financial viability of such schemes and attracting developers. Because these require new models, and because industrial space commands lower prices than residential, developers are likely to be reluctant. Investment and support from both the GLA and local borough authorities may therefore be needed to develop proof of concept examples in the city.

Increasing demand for industrial space

Vacancy rates on many industrial sites across the city are low or very low. In the case of the popular Park Royal estate, vacancy rates have fallen to as low as 2 percent. This is due in part to the loss of industrial land across the city, but also as a result of new demand from the growing ‘just-in-time’ economy, whose need for warehousing and logistics space is contributing to an already stretched capacity. London is also experiencing an increasing demand for industrial space from e-tail and e-commerce companies who need it to provide next day (or even next hour) delivery to residents and businesses across the city. Even within industrial sites, the manufacturing sector is competing for the available space with a host of other industrial uses. Demand for warehousing and logistics is likely to grow so it will become increasingly important that industrial space is able to cater for the wide range of sectors for which it is vital. Manufacturing must have a voice in that discussion.

2 Giving makers a voice and making them visible

Despite employing over 110,000 people within London, the manufacturing sector lacks visibility. Its activities are found across the city, however they often take place in locations that are out of sight to Londoners, in industrial parks or behind unlabelled doors. Most residents have no idea what is made in their borough and many Londoners’ perceptions of manufacturing may be anachronistic and not reflect the true nature of industry today. There is a danger that manufacturing could suffer because it is unfamiliar. A lack of interaction may lead to misconceptions about what manufacturing is and does, which could have negative impacts on skills development and retention within the city.

This perception can be powerful and it is not only residents who are unaware of the activities taking place. The same challenge faces local and regional authorities. At a recent GLA Planning Committee hearing, concerns were raised about planning officers’ lack of understanding of the sector and its requirements. This is particularly concerning as they take important decisions which affect the future of manufacture in London.

Precise, centralised and accessible data about numbers of firms and where and what they are making is lacking. There have been a number of in-depth studies carried out on particular industrial estates, such as the Park Royal Atlas, and these provide fascinating and useful insights into the detail of the activities taking place. However, these studies are concerned with a small proportion of London’s industrial activities, and given that manufacturing is but one activity taking place on industrial sites, there is even less information specifically about manufacturing. The data from these reports is generally to be found within pdf reports and case studies rather than in more easily searchable formats. This limits their ability to be searched or aggregated by local authorities, researchers or other organisations seeking to understand the sector.

It is important that policy makers hear the voices and concerns of the sector. However, given that London’s manufacturing base is made up of many small organisations it can be challenging for these diverse organisations to be heard. The size of these firms means it is likely that they are focused on their own daily activities and may lack the resources or connections to engage with policy makers or developers. Organisations and bodies to provide platforms for the collective voice of manufacturers are therefore particularly important. This includes sector organisations like EEF and Soloman, and place-specific organisations, like East End Trades Guild, or Industrial Business Improvement Districts. This collective voice is particularly important when it comes to the spatial planning arena where large, often multinational, stakeholders dominate the field and technical language can make it difficult for non-experts to engage in discussion. There is a significant power imbalance between these groups and it is important that the concerns of London’s manufacturers are heard, whatever their size. East End Trades Guild, for example, are calling on prospective local councillors to support their Affordable Workspace Manifesto, which lays out ambitions for a London Working Rent for workspace.

3 Building connections and capacity for innovation

Lack of visibility also affects manufacturers’ ability to connect with one another or with potential clients. Interviewees frequently cited concerns about the lack of connectivity and capacity in London’s manufacturing base. These issues both have potentially significant implications for the future prosperity of the sector and of the wider economy as they threaten to dampen opportunity for new business and innovation.

London has enormous potential for fostering innovation. The UK and London develop excellent designers, but these designers must also be able to take products to market. Creating strong relationships with industry, which has the technical knowledge, is vital for enabling this. The purpose of the Central Research Laboratory (CRL) in Hayes, who run an accelerator programme for start-ups, is to prove that the supply of talent and skills in London are such that you can run an investable and sustainable hardware business. They are working on innovations from science education kits to cleantech. When it comes to manufacturing however, these businesses, and others, go outside of London and the UK, often to China. One interviewee likened manufacturing in China to going to the supermarket “we know we can find everything and everyone we need”. They likened the same process in the UK to “making your way to a farm and being told ‘there might be some carrots in the field’” – neither the infrastructure nor the work is easy to navigate. This was not to criticise the local firms, rather to highlight a lack of support over time resulting in manufacturing infrastructure that is feared to be too fragile to deal with the potential that exists in the city. Things are ticking along, but there is a lack of dynamism. Others share similar concerns, believing that this fragility leads to defensive behaviours; people are reluctant to share their manufacturing connections in the city for fear that they themselves might lose out on capacity. Potential for growth and innovation are slipping through the gaps. Given the ambitions set out both in the Industrial Strategy and in the London Plan, improving the situation is an opportunity that should not be missed.

Support to broker relationships could help to address this. An example of this from outside the capital is Make Works. Beginning in Scotland, but now rolled out across a number of cities, the organisation facilitates connections between manufacturers and designers, with the aim of igniting new working collaborations. London’s makerspaces could also play an important role through opening up routes to making. However, they themselves face challenges in developing sustainable business models and securing workspace. It is worth exploring how London can support these spaces. Barcelona’s Fab City approach is an interesting model for this as it brings together the city council, private business and makers to explore how local production can support the city’s future.

Education and skills are also critical, and whilst better accounts exist of the need for improving the supply of skills for the manufacturing sector as a whole, suffice to say this applies equally to London’s workforce and education system. And whilst London can be an attractive place for a business, it is an expensive place to live for its staff. Despite its success, Brompton has found it challenging to compete for skilled engineers against other parts of the country where the cost of living is lower. The city needs to find ways to grow, maintain and attract skilled workers for its manufacturing sector.

An investigation of the links within industry was not the main focus of this work. Nonetheless it hints at a challenge facing the sector and one that may significantly hinder its future. More investigation is needed into the interconnections within London’s manufacturing base.

4 Making it sustainable

Policy makers, residents and businesses are recognising London’s urgent need to become more sustainable across all of its many activities. Manufacturing has a key role to play in this future and needs to be involved more in these discussions.

Practical investigations into developing and implementing a more circular economy within London are underway. In 2017, The London Waste and Recycling Board (LWARB) released a route map proposing five focus areas for circular economy opportunities: food, built environment, electricals, textiles and plastics. By 2036, it is predicted that circular economy developments in these sectors could provide London with net benefits of at least £7bn every year, as well as 12,000 net new jobs in the areas of re-use, remanufacturing and materials innovation. As part of this work LWARB and partners are working to provide business support, develop sector knowledge bases and encourage collaboration between stakeholders. Practical investigations of this kind are key to better understanding the networks involved and the support needed to unlock the potential in the city.

Policy makers need to continuously engage with this developing knowledge in order that policy can accurately reflect the needs identified. The current policy picture is not yet comprehensive. Whilst the high-level policies described in chapter 3.3 acknowledge the relationship between the circular economy and business competitiveness through improved resource efficiency, they demonstrate little understanding of how that potential can be unleashed through links with the manufacturing sector in the city. There is, for example, limited discussion about how recycled and secondary materials will be incorporated back into local productive cycles in the city, or of the economic potential of those resources. The London Plan explicitly encourages exemplar case studies of circular economy practices, such as extending product lifetimes, the production of secondary materials, and repair, refurbishment and remanufacturing activities, but provides no indication of how these activities may compete with other uses in the city. Given the current spatial challenges for industry in London, this needs to be given due consideration.

If London is to meet its sustainability ambitions it needs to look at its current manufacturing sectors and ask if it has the skills and technologies required to transition to a more circular economy. Both existing and new manufacturers can be supported in developing products and services that support this. Mobilising around this challenge would provide an exciting opportunity to develop skills and harness technology within the city.

5 Creating a vision for manufacturing

London’s manufacturing sector will continue to evolve, shaped by new technological developments, consumer demands and political choices. A new wave of technological change is on the horizon and London should take the opportunity to consider what role it wants its manufacturing sector to play in the city’s future, as well as what policies and initiatives are needed to facilitate this. Perhaps not all manufacturing that could be based in London, should be based in the city. Space is limited and the Industrial Strategy is seeking to rebalance economic growth across the country. Within its own vision for manufacturing, London needs to consider its relationship with other parts of the UK.

However, there are activities that need to remain. The city’s residents and businesses need goods and services that enable them to go about their lives and activities. There will always be a need for the local manufacturing businesses that provide produce perishable and time-sensitive goods, or specialised methods of production. As the city grows, this demand is likely to increase. Take the large food sector in the city, or the printers and set makers.

In addition to this local demand, London’s ability to draw entrepreneurs, investors, and a creative and educated workforce provides a huge opportunity for innovative manufacturing businesses to start. These businesses are attracted to London’s unique business climate and the city should recognise the value that they bring in both employment and innovation. The draw is illustrated in the decision by The Albion Knitting Co. to set up in London. Despite there being more traditional locations in the UK for knitwear, Albion chose London to be close to both its clients and to a dynamic workforce. London should consider its opportunity for incubating new manufacturing businesses. Some, such as Brompton, may then continue to stay in the city as they grow. Others may choose to move elsewhere.

London’s vision for manufacturing in the city should be based upon a sound understanding of its value and an appreciation of its economic and social connections. London’s manufacturing community should be involved in shaping this vision.

This text was first released within the ‘The Cities Report‘.