Profiles: Mark Brearley – Kaymet – London

Photo © Southwark News.

For Mark Brearley, becoming a manufacturer was a happy accident. He went to buy a tray from a small urban manufacturer, and a few months later it became a two-family business, his and Mr Schreiber’s. They make aluminium trays, about 20,000 per year, from their Peckham base. As he explains, they are just one of many businesses in a sector which London should celebrate and support.

We started in the basement of a radio shop in the 1930s and became Kaymet in 1947. A classic story of city enterprise. Four years ago, the business nearly evaporated, but now sales have more than doubled, to 40 countries, and the team has grown to ten. We are proud to have been in our part of South London for 70 years, contributing to the diversity of the area’s economy. Yet the storm clouds are brewing. Southwark Council want all the industry around the Old Kent Road to go away, they want housing to push us aside. This threatens several hundred businesses, a few thousand jobs.

Our story is typical of London now. A production economy that had been written off, assumed to be in terminal decline, but has in fact returned to growth, alongside the rest of our city’s industry (11% of London’s jobs, close to half a million). I have been making a list of the capital’s manufacturers, it is now 2800 entries long.

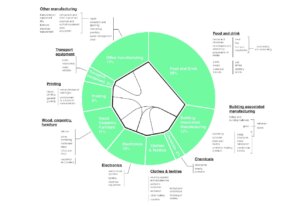

Ford’s diesel engine plant in Dagenham, our biggest factory, makes over a million engines each year. They are increasing production, growing the workforce to 2250. But they are an eccentricity, the only maker with more than a thousand people. The scene is dominated by small businesses, and its remarkably dynamic and diverse.The majority are hooked to the London market, producing just-in-time and bespoke stuff ranging from sandwiches to scenery. All of this can be expected to grow strongly as London’s population expands. The city will need more, not less. We will need more wood workshops and stone cutters, alongside food preparers. These trends are magnified by increasing prosperity and burgeoning interest in local origin. For example, the bespoke tailoring industry has reversed many decades of decline, with the city now boasting well over 50 such businesses.

Baking is a fast growing industry, and high volume bakers are expanding their London facilities. Warburtons in Edmonton now runs around the clock throughout the year, making 23,000 loaves per hour. And, with blossoming appetite for craft baked bread, the number of smaller wholesale bakeries has been increasing, to about 130 currently. Brands such as Konditor & Cook and Blackbird Bakery have become significant London producers.

In fact, food production has been the fastest to evolve, capitalising on the strength it has long gained from a culturally diverse population. Following the craft beer and coffee roasting phenomenon London now has new distilleries, doubling its count to six, soft drink producers, a dozen new chocolate makers, plus a huge number of niche food preparers.

London’s expanding concentration of people interested in luxury, and many who combine liking a metropolitan lifestyle with high technical or creative skill, plus entrepreneurial drive, is also influencing making in the city. Four paint producers, six gun makers, one tray and three brush manufacturers, seemed anachronistic until recently – now they are each reviving and re-positioning. New companies are emerging alongside. Dunhill, Hanson and Tanner Krolle were amongst the few surviving branded London luxury leather goods producers, but now they have been joined by about 20 newer producers such as Tallowin and Thomas Lyte. These businesses are flourishing not just because of the London market for goods (which could be served from elsewhere) but also because the people with the desire and the skill to produce want to be here.

The city’s denuded garment manufacturing capabilities, coupled to a vibrant design scene, are now providing a fertile base for growth. Clothing brands have been the fastest to embrace Made in London as a major asset. Volumes produced are increasing – it is possible to identify around 100 workrooms. While once it might have seemed just quirky that military dress uniforms are produced in Tottenham, and ceremonial hats in Bermondsey, now it’s an indicator of London’s exciting potential for manufacturing growth, as is the chance survival of four mannequin makers.

London is likely to lose a few larger process plants, indeed a couple have closed in recent months, but the job losses involved are not massive. Nestlé did away with their Hayes coffee factory, shedding 230 jobs, and closure of InBev’s Stag Brewery in Mortlake snuffs out 180. These are examples of what’s happening with making in London. While it had seemed likely a few years ago that we would become a one brewery city (Fullers at Chiswick), in fact over 40 new breweries have emerged, with a handful (such as Meantime and Camden) dramatically up-scaling. The jobs generated thus far by these generously exceed the loss of InBev from Mortlake. Likewise, the rapid growth of small coffee roasters, so that now London has over two dozen wholesale roasteries, looks set to more than compensate for the loss of Nestlé.

And then there are global shifts helping us. Many have fond memories of painting plastic models with Humbrol enamel paint in mini-tins. Long made up north, a few years ago they shifted production to China, like people did. Then, exasperated by quality and delivery problems, they put out a call for a UK contract manufacturer. Now it’s made by Rustins in their small Cricklewood factory. This is part of a major trend to re-shore, to localise some production.

Meanwhile Caterham are booming making cars, and so are Brompton, making bicycles. Furniture production, that seemed doomed just a few years ago, is growing once again, with now around 130 small-scale makers. And, of course, we have four thriving umbrella makers, plus paper bags, wax, sugar, processed rice, edible oils, ladders…it goes on.

But all is not well. Competition for space is intense. London is being stripped-out. Housing growth is removing the capacity for a flexible and vibrant everyday economy. We are now seeing an accelerated suburbanisation of much of London beyond the centre, a shrinking of chances, an increasing mis-match between the city’s vibrancy and its physical fabric. Industrial activity is being hit the hardest, and makers are not at the top of the value hierarchy. If it comes to a punch-up the bus garages, rail and courier depots, trade counters, will win. We will lose. To cut a long story short, we are hurtling toward a shortage of industrial accommodation unless we shout out and secure some action.

My feeling is that we need to celebrate, make visible, win the public around, at the same time as pushing the policy and decision makers, campaigning and arguing, explaining why a good city has industry, and how such a city can be sustained. We need to state our belief that manufacturing is a vital part of our city, indeed of any good city, that should be visible, understood, celebrated and nurtured. Cities are the home of innovation and entrepreneurialism, a great crucible of the new. That includes making, now on the up, popular and viable once more. It is time to embrace production in the metropolis, to realise that we need it, and shout out that we want it.

We interviewed Mark for Cities of Making – our programme of work investigating the role of urban manufacturing in European cities. First appeared on the www.thersa.org on the 22nd of May.