Think Manufacturing in London Is No More? Think Again.

Opendesk wood cutting space / ©Opendesk

How can we support an innovative and resilient manufacturing base in a city? This question is central to a current RSA project, Cities of Making. Together with UCL, we are looking at London, while our European partners will do the same for Brussels and Rotterdam. A crucial first step is to understand what London’s manufacturing looks like. Is there any left? And what challenges does it face?

Among London’s rich history of trade and finance it is easy to forget that it was once an industrial city. The clothing, leather, hat and shoemaking industries were important to the East End, and other industries from watches and precision engineering in Clerkenwell, to shipbuilding on the Thames, to motor vehicles in Vauxhall, have come and gone from the metropolis.

But surely that is all in the past?

Well, not really. This blog explores what the data tells us about manufacturing in London today.

While London’s economy is clearly not geared towards manufacturing, we should not be too quick to write it off

Most people are aware of this but what we don’t always point out is that London has a vast and diverse economy. Manufacturing is just one small part, accounting for 2.3% of total employment and a similar share of GVA. However more people are employed in the sector (116,000) than in other UK city regions such as Manchester and Leeds. At £8.4bn, its GVA output from manufacturing is similar to Wales.

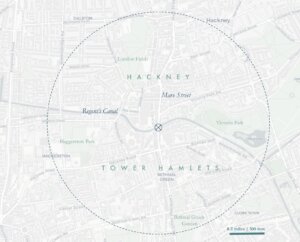

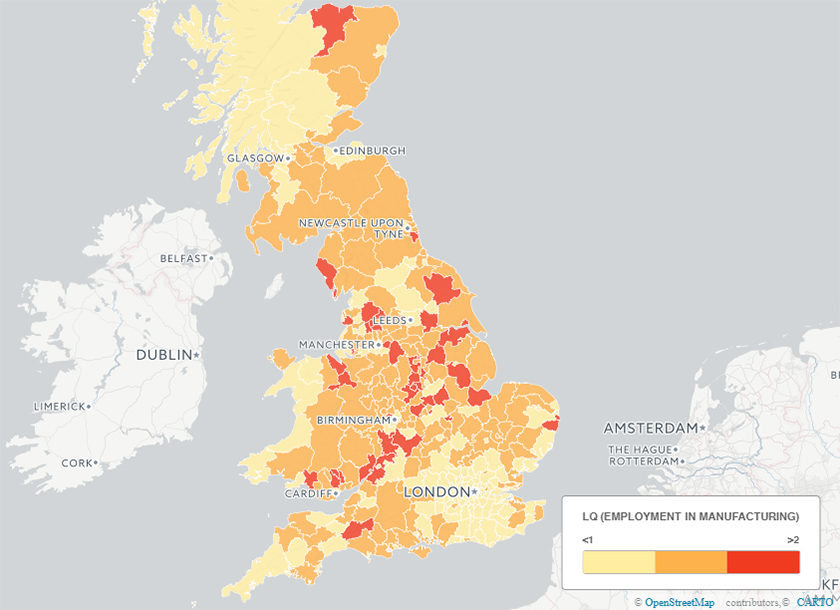

Figure 1: Relative concentration of manufacturing employment in Britain. Source: RSA analysis of Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES), 2015

Arguably, the real cities of making in the UK are Sunderland, Hull and Derby with more than 17% of their workforce employed in the sector. Location Quotients (LQ) indicate how concentrated an industry is relative to the UK. With LQs greater than 2, workers in these areas are more than twice as likely to be employed in manufacturing. So why focus on London? Well, if breathing new life into manufacturing is possible here, it might just be possible in any city in the UK.

But history has taken its toll

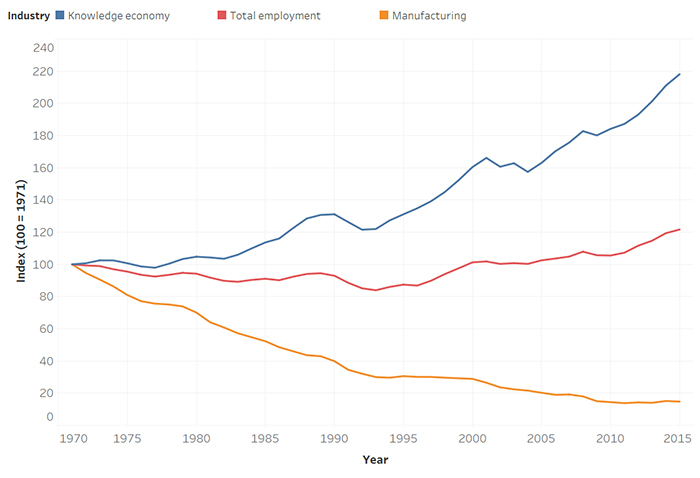

Since 1971, when manufacturing accounted for 17% of jobs in London (or 870,000), the sector has shrunk by 85%. While most of the damage was done before the 1990s, the hollowing out of the sector continued until recently. Meanwhile the knowledge economy, here defined as information and communication, finance and professional services, continued to grow.

Figure 2: Changes in London’s employment composition since 1971. Source: ONS Workforce Jobs, GLA estimations and RSA calculations

De-industrialisation, offshoring, financialisation and a move to a service based economy all had a role to play. In more recent years, there are signs that increased productivity, perhaps due to new technologies, has cushioned the blow for manufacturers. Since 1998 total hours worked halved while output per hour grew by more than 40%, meaning London’s manufacturing GVA output suffered a less drastic decline.

London is more about small scale manufacturing than other places

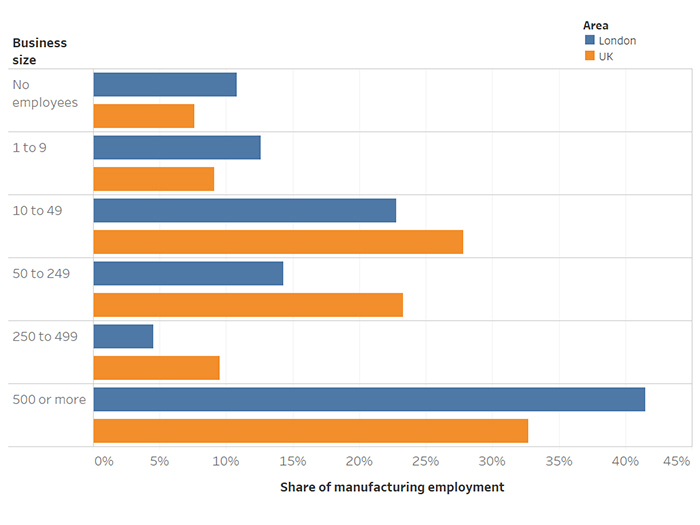

Compared to the rest of the UK, London’s manufacturing workforce are more likely to be self-employed (a business with no employees) or work for a micro-business (with 1-9 employees). They are also more likely to be employed by a very large business (with more than 500 employees). This suggests that, apart from the behemoths already located here, it is more difficult for London’s manufacturers to scale, and take the step from self-employed or micro-business (SEM) to small or medium enterprise (SME).

Figure 3: Employment in manufacturing by business size, London and the UK. Source: RSA analysis of Business Population Estimates, 2016

A shortage of appropriate industrial space, driven by demand for housing, may be an obstacle. Our analysis of Valuation Office Agency (VOA) data shows that London has more property units, known as hereditaments, per m2 of industrial floorspace than other UK regions. In other words, manufacturers in London typically have less space to work in. The cost of this space is also more than twice as expensive as other parts of the UK.

So what hopes should we have for the future? Could London be an incubator for the UK’s manufacturing innovation eco-system, where the design and prototyping of new products takes place? This seems a realistic prospect, given that the city is a hub for auxiliary industries relating to design and computer programming, accounting for 33% and 28% of the UK’s total employment in these respective sectors.

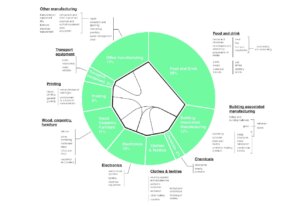

London excels in food and clothing – but do we want it to?

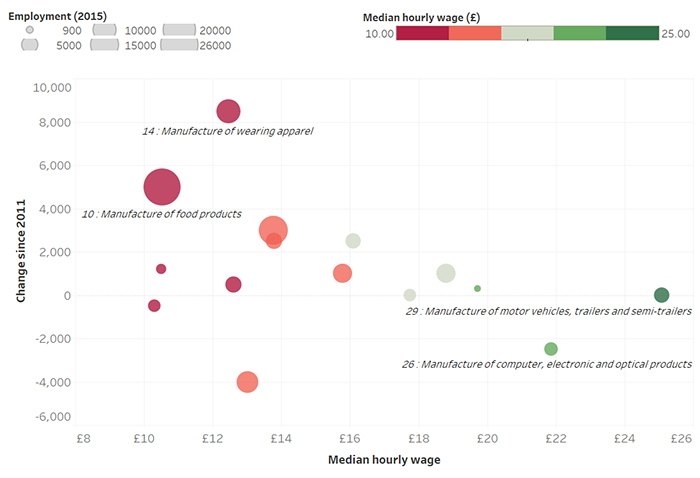

Manufacturing jobs are perceived of as higher quality than those in retail and hospitality where huge swathes of the workforce are poorly paid. While this is true to an extent, we should be careful about the kinds of manufacturing we promote. 21% of London’s manufacturing jobs pay less than the London living wage (set by the Living Wage Foundation at £9.75 per hour).

Figure 4: Pay and employment growth across London manufacturing sub-sectors. Source: RSA analysis of BRES and the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE)

Manufacturing sub-sectors vary significantly in the skills they require and this is reflected in pay packets. Food and clothing – two goods that are ‘close to the consumer’ – are having something of a renaissance in the city. However typical workers in these sectors earn considerably less than those who make cars or computers. Food manufacturing may be especially guilty of providing poor quality jobs – our analysis of ASHE shows that 43% of employees earn less than the London living wage – a figure no different from retail.

A tale of two cities

London still has a future with manufacturing, albeit one that may be different to what people expect. But as the RSA’s Josie Warden has argued, we need to avoid falling into nostalgia traps. As part of the Cities of Making project we will try to demystify the industry and put forward a vision for the future of urban manufacturing. London is more sandwich making and less steelworks – more about food and fashion than high value aircraft or pharmaceuticals.

But it’s not all about hipsters and craft beer either. We see potential for a broader range of innovative smaller scale manufacturing in the capital but to realise this will require a supporting policy environment.

Despite a lack of direction, the sector has been plodding along, with some good and some not so good outcomes. London could do better. The city needs a new vision that is based on pragmatism, and which makes the most of its existing strengths – be it the capital’s heritage, skills or supply chains.